sucrose.

The exhibition of my MFA thesis show, sucrose, contained work that explores identity and image in an increasingly digital world. There is a tension I feel as both a woman and an artist between a desire for authentic connection and consumption. There is a pressure to commodify myself, commodify my art. There is a pressure to find myself through the things that I consume, to aestheticize myself over embodying myself. There is a push and pull that I feel in my own performance of myself that comes out in my process and the images I create.

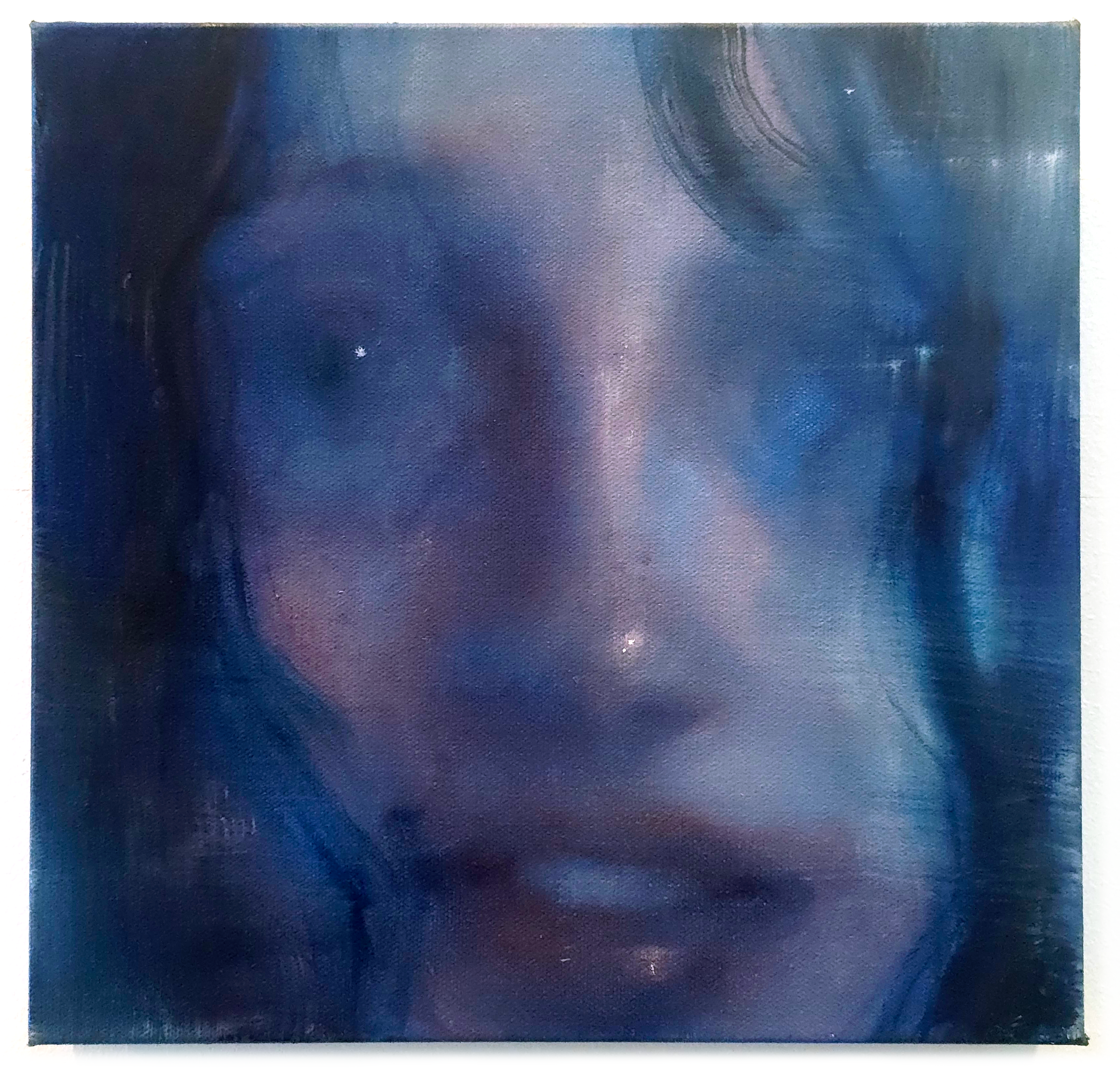

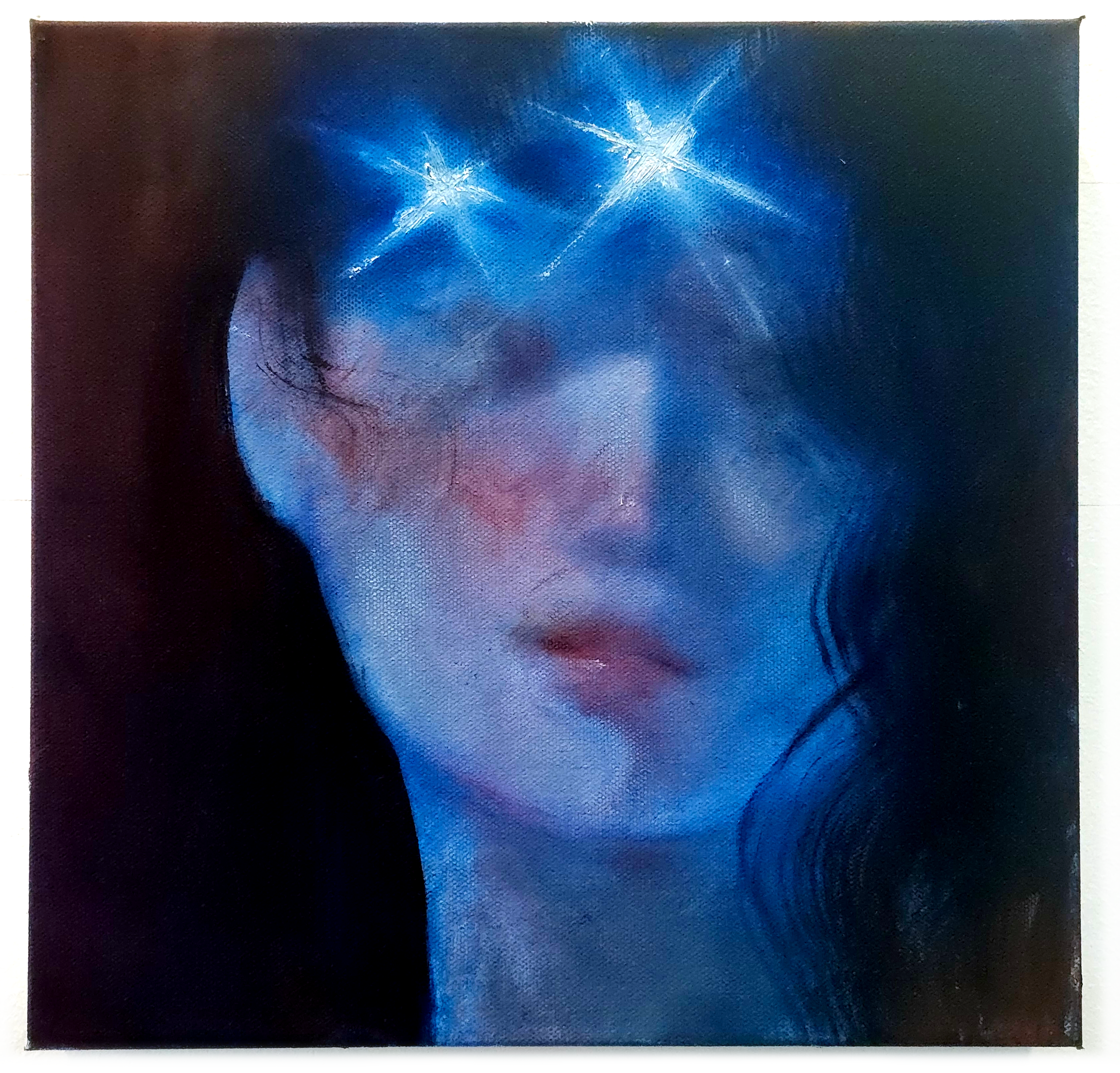

The work of this thesis is figurative, but the portraits are not interested in capturing the essence of the person depicted. The parts of the face become something more like a landscape to explore an internal psychological experience. The subjects are often not real people, but imagined composites built from fragments of online imagery. Some are references to memes and viral visuals that repeat in excess.

I work in oil because I’m drawn to the medium’s slowness and its capacity for layering. Each painting becomes a process of searching, building, obscuring, and revealing until the image feels alive but unsettled. I’m interested in that in-between state, where something feels simultaneously intimate and unreachable.

Through these explorations, I aim to create work that reflects the complexity of contemporary identity, inviting viewers to consider the parasocial way we can see ourselves and each other in a world saturated with content and images.

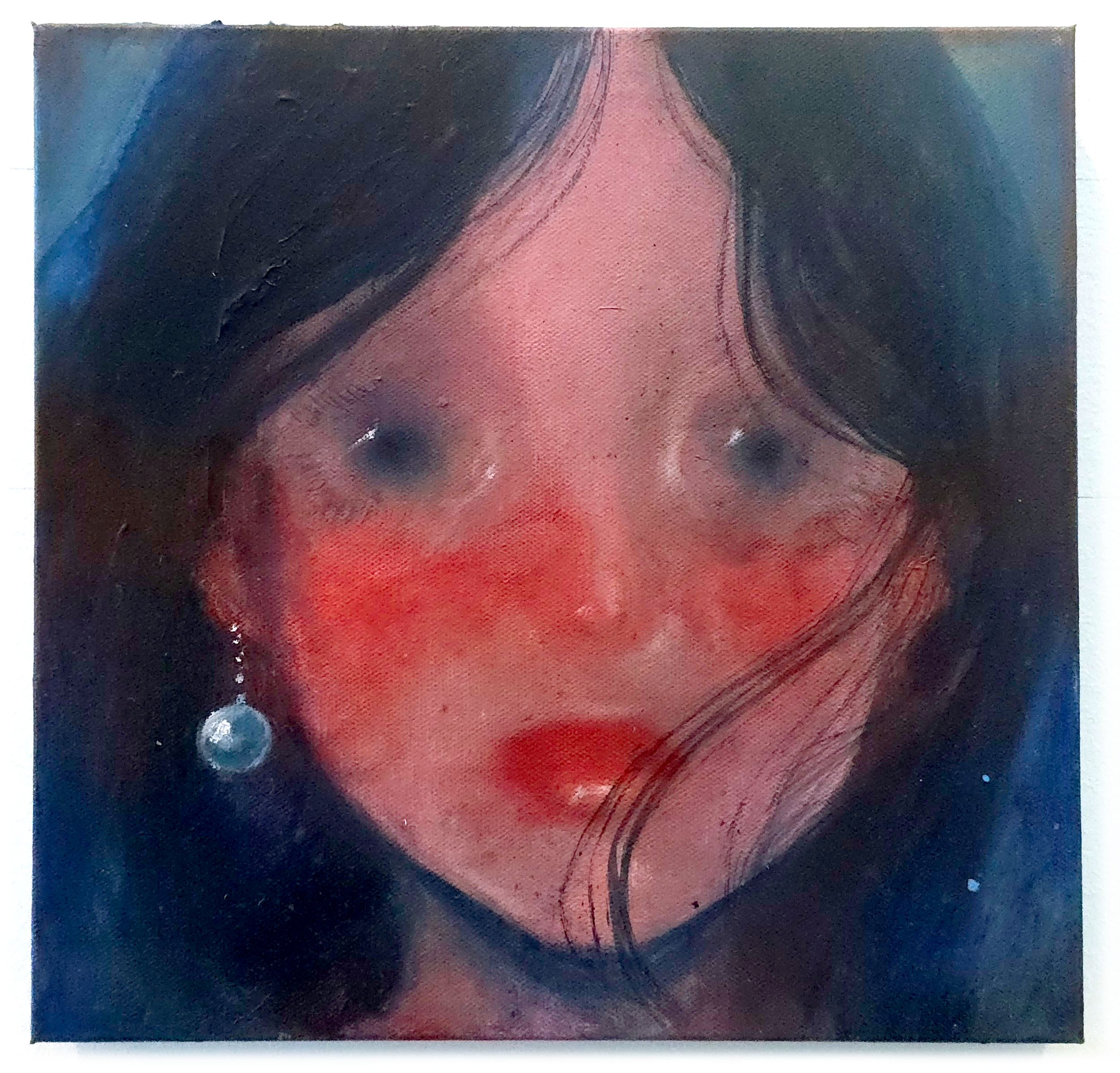

Stranger, 2025, oil on cotton, 12 x 12 inches.

For reference, I would pull images from various corners of the internet. The work became about the search for identity through modern means: popular social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok.

I selected images that already felt removed from the person being portrayed, such as viral images, memes, and targeted advertisements. Since I am the one sourcing these images, it is also a reflection of the kind of content I receive through my own personal algorithm. In that way, it becomes another self-portrait, reflecting the way I personally interact with the media that is presented to me. However, it is also a portrait of the identity that is sold to me through advertisements targeted at my demographic.

John Berger elucidates the relationship between the spectator-buyer and the publicity that is presented to them in Ways of Seeing. He states that glamour can only exist in a society where envy is a widespread emotion. Glamour is the state of being envied, and publicity is the process of manufacturing glamour. With these ads, myself as the spectator-buyer is meant to imagine myself transformed by the product advertised into an object of envy for others, which is meant to justify my loving myself.

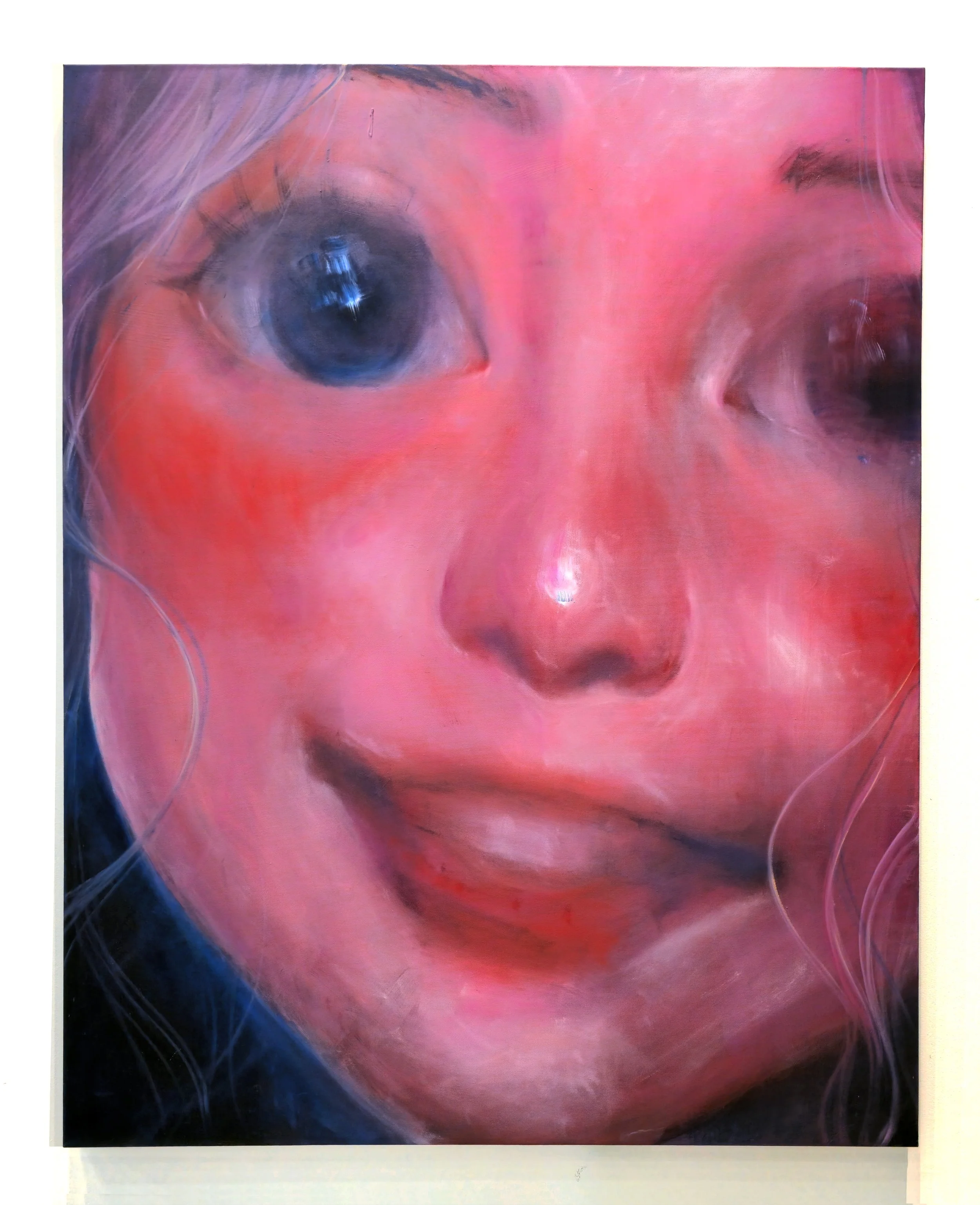

Sucrose, 2025, oil on cotton, 60 x 45 inches.

Sucrose was referenced from a screenshot of a clickbait ad on Snapchat about Kylie Jenner, a member of the Kardashian family. The Kardashians have famously built an empire on glamourizing themselves. Jenner’s face and body reflect the cosmetic procedures she underwent as a teenager in order to better perform her role as a symbol of beauty culture within her family, alterations she has since expressed regret over. This image stood out to me as an exemplification of the way a pursuit of external beauty is pressed upon young women.

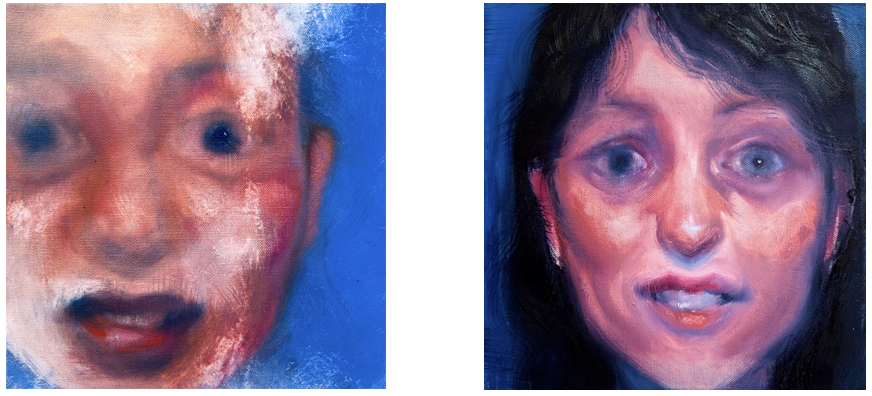

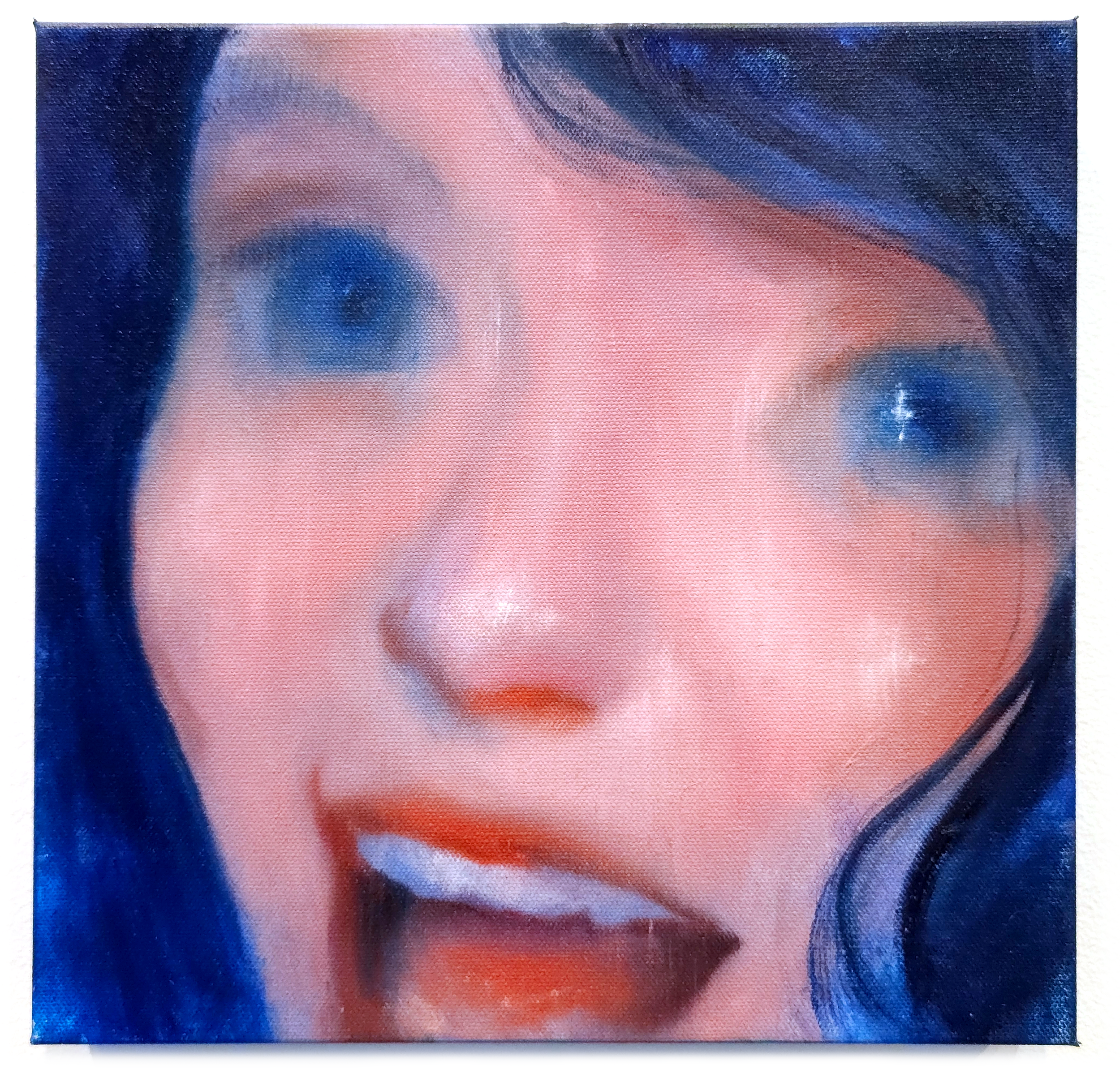

Glucose was referenced from a screenshot of the most liked TikTok video at the time: a ten second video of a woman named Bella Poarch lip-syncing and making cartoon-like expressions, such as crossing her eyes. I was drawn to this image for its emptiness, it’s separation from any sense of Poarch as a person, and its immense appeal regardless.

These paintings together reference two sides of the same mechanism. One side is the reductive consumption of a young woman’s image as entertainment, the other being the pursuit of a particular image of beauty being sold to young women. Both Jenner and Poarch become symbols rather than subjects in these images. Their identities have been overshadowed by ideals of visibility, desirability, and algorithmic appeal. Both point towards the way modern visual media creates an economy of consumption, a feedback loop where young women start to see themselves as images rather than identities. As Berger put it, stealing the love of the viewer for herself as she is, and selling it back to her in the form of a product.

Glucose, 2025, oil on cotton, 60 x 45 inches.

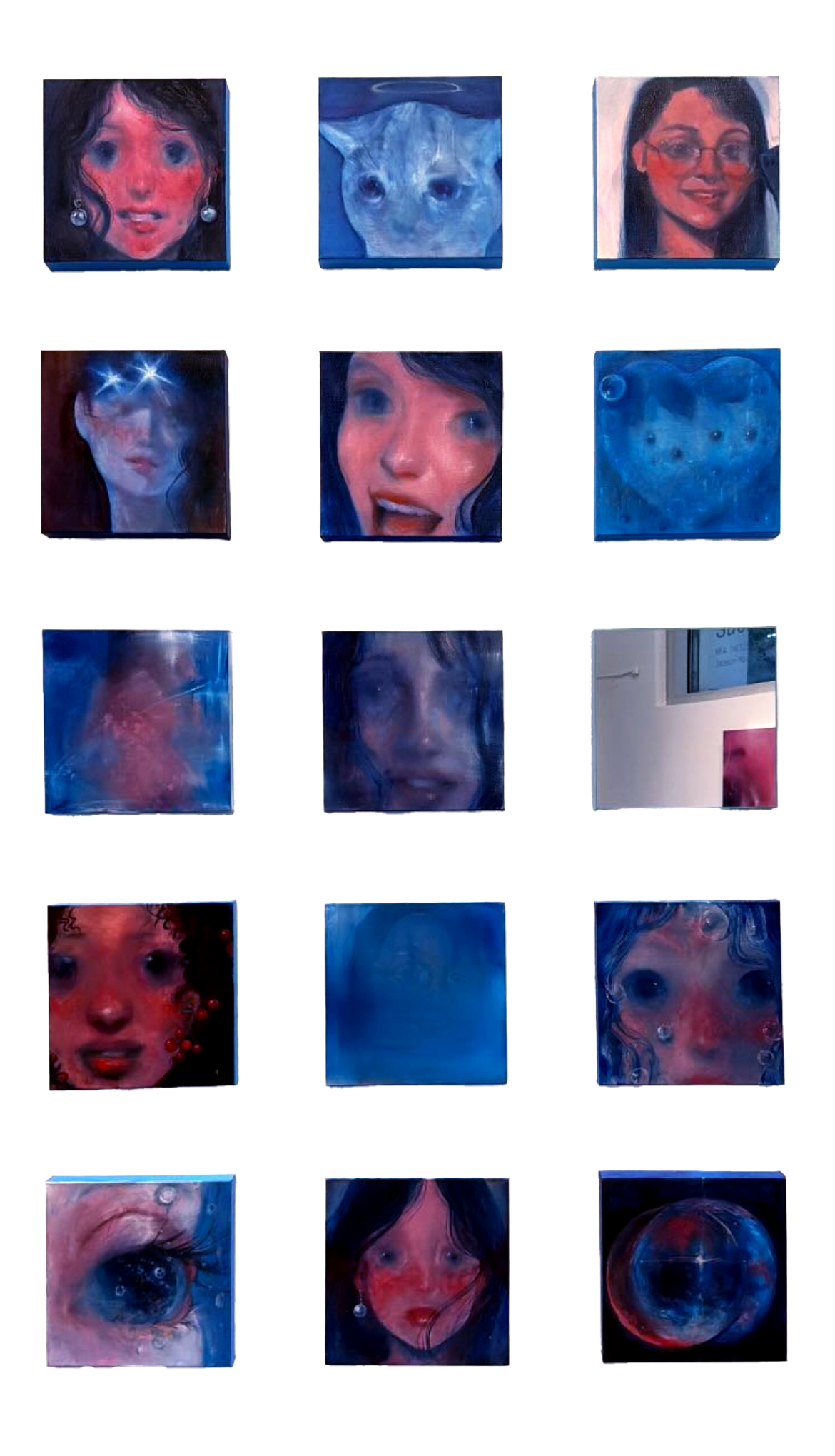

The Grid, 2025, oil on canvas and mirror on panel, 84 x 48 inches.

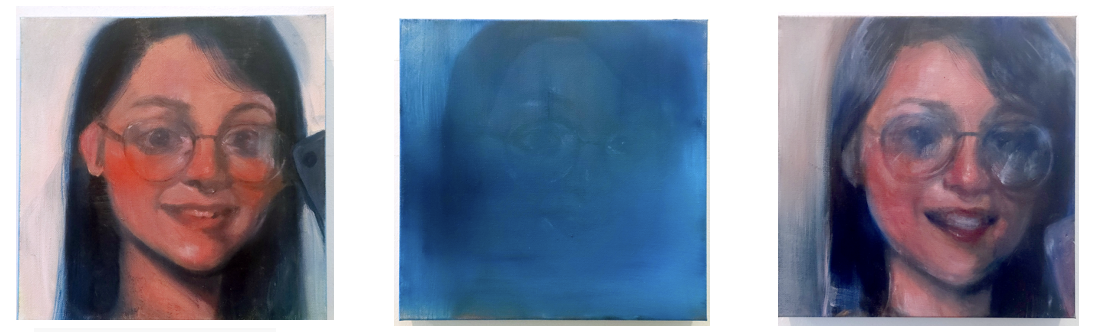

The Grid is the culmination of my exploration into images from social media. The Grid is a piece comprised of fourteen individual 12 by 12 inch paintings and one 12 by 12 inch mirror on panel. Together these images were intended to function as one piece.

Hanging the images in a painting format places each image in relation to the image next to it, allowing the eye to bounce from expression to expression and putting each person in the context of a larger whole. I was interested in the way that within the context of the grid, each individual portrait’s identity becomes enmeshed with the others, but also distinctly separated into their own picture planes. The portraits also show my process. Some parts of the image appear to have been made quickly, while others were done through extensive trial, error, and exploration. Many of the features of these portraits blur away, parts are left loose and unfinished. It is also visually meant to mimic the feeling of an Instagram grid or social media explore page.

At eye level, I placed a mirror, to bring the viewer into the work as a part of the piece. Since the work is ultimately about identity, the mirror is a reference to what Lacan theorized as the mirror stage: the stage in human development where we recognize ourselves in our reflected image, which creates our initial sense of identity. Placing this mirror in the context of the digitally sourced images in the Grid references how we are also forming our sense of identity within the context of social media. (I was also hoping people would take mirror selfies in it during the exhibition, to post them back into the world of social media, completing a loop of image from internet to life, then back to the internet.)

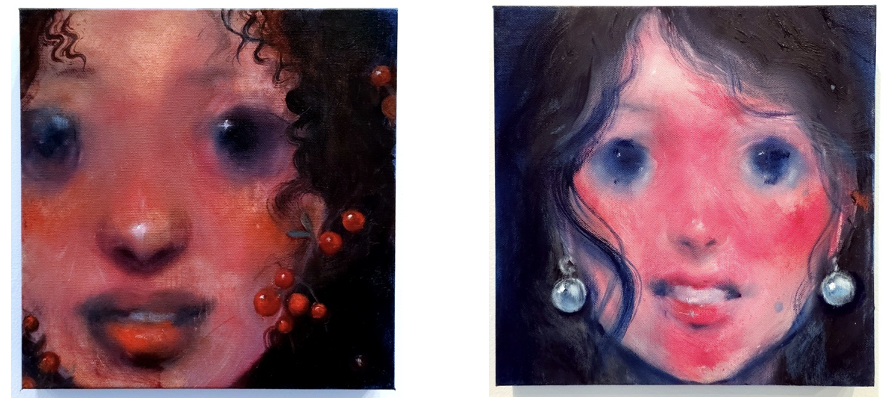

Some of the first images within the Grid started out as studies from thispersondoesnotexist.com. As I created more pieces for the Grid, I also added layers to these portraits. What became of it was a slow filter. I blurred away lines of the nose and eyebags, enlarged the eyes, reddened the cheeks, adorned them with pearls and berries. These were choices influenced by filters built into social media apps like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok that are intended to alter the features of and beautify the user. The results, Berry and Pearl, were images that barely resembled the originally referenced faces.

Within the Grid there are paintings in which I referenced my own image. These are all self-portraits based on a mirror selfie of myself from 2017. Their inclusion in the grid implicates me within this landscape. My own forced smile and my own face distorted every time I repainted it.

Blush Blind is a self-portrait that followed the same layering process as Berry and Pearl. The title references the phrase, which means you can no longer perceive how much blush you’ve applied, having been visually numbed by trends.

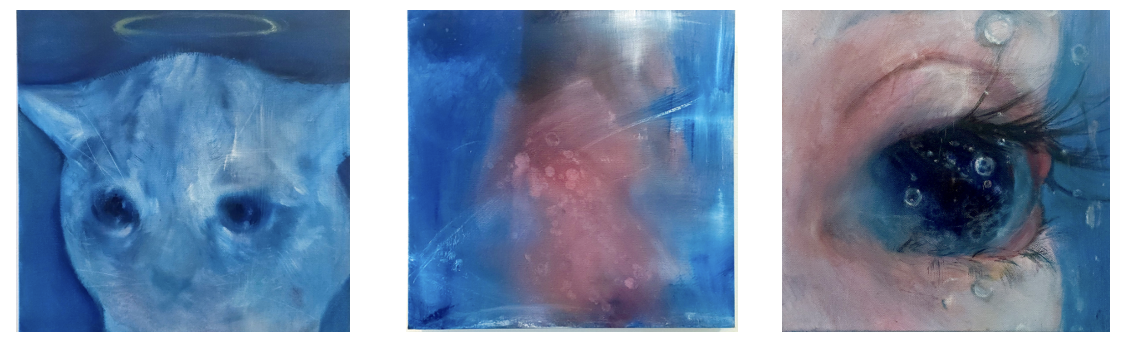

Surrounding these images of myself and women that did not exist, there are many images sourced from Instagram and other social media platforms. Angel was from a ubiquitous sad cat meme. Mirror was from a bot account on Instagram, catfishing as a young woman in a bikini to try and get you onto onlyfans. Eyedrop was from a clickbait beauty article about lashes.

Crystal is a piece formed without reference, from my imagination, influenced by all the pieces around it. In the same way artificial intelligence forms images based on the images put into it, I formed this image from the images I’d been referencing.

Each of these disparate images, put together, feel like they emulate the whiplash of images that the digital age offers.

None of these paintings are a one-to-one replica of the source material. My interest was not in directly appropriating images like Richard Prince. It is important that they have been morphed through the process painting into something else. A screenshot, especially of a clickbait ad, is a disposable image not meant to be lingered on for long. The process of oil painting slows down the replication of the image. I am sitting with the image, staring at it, for much longer than was the intended. Through my focus and my hand, I make choices on what to bring into focus, and what to leave unresolved.

In the form of a low-resolution screenshot, the image functions as what Hito Steyerl would call a “poor image”. Poor images, according to Steyerl, are popular images that express the contradictions of our contemporary society: “its opportunism, narcissism, desire for autonomy and creation, its inability to focus or make up its mind, its constant readiness for transgression and simultaneous submission.” Poor images are not about the original content of the image, as much as it’s about the conditions of the image’s existence. The poor resolution, pixelation, and blurriness becomes a class position, as being out of focus lower’s the value of the image. In my paintings, the blurring I originally incorporated in my paintings to reflect the instability of identity is also representative of the lack of detail in the source material.

Through my exploration into painting human figures, I’ve reflected on how our time is reshaping our perceptions of beauty, identity, and lived experience. My work questions how digital culture and image saturation influence not only how we see others, but how we see ourselves. Situated within the history of portraiture and other contemporary artists exploring similar subjects, I have painted people that do not exist, viral images, modern symbols of beauty, memes, and myself.

These paintings seek explore my own identity in our modern world of images, where self-commodification has become a pervasive norm. I named this thesis sucrose. after the scientific name for a naturally occurring disaccharide that is processed and refined into the sweet, crystalline substance we know as white sugar. Like sugar on the tongue, the consumption of images online offers a fleeting sweetness and a hit of dopamine. The figures in my paintings present the struggle between authenticity and artifice. In eye contact they share with the viewer, they ask: do we seek genuine connection, or are we content to be consumed?